With its cowboy lettering, metal handles and combination lock, the Weatherford Hotel antique vault looks like something in which the bad guys would be very interested, but this substantial piece of territorial history has done its job, safely protecting treasures for more than a century.

With its cowboy lettering, metal handles and combination lock, the Weatherford Hotel antique vault looks like something in which the bad guys would be very interested, but this substantial piece of territorial history has done its job, safely protecting treasures for more than a century.

In the late 1870s, business was booming in Arizona. With cattle and sheep ranching, farming, timber harvesting, mining and the growing railroad industry, jobs were plentiful and cash was flowing. Individuals and businesses needed to store money, precious metals, jewelry and important papers that documented births, property ownership, stock certificates and business transactions.

Vaults the size of hefty refrigerators served banks and other businesses. They had to be heavy enough to keep burglars from carrying them off – the Weatherford’s weighs a couple of tons. They had to be able to survive a fire – many of the buildings were made out of wood and a lot of them burned down. And they had to be complicated enough to outsmart or discourage a thief – the hotel’s vault has drawers inside it that were all keyed differently, as well as a thick outer door secured with a roller bolt combination lock.

Ornate facades commonly adorned such vaults and often reflected the Victorian era style. Extensive etching and painting commonly displayed western scenes. However, the Weatherford Hotel vault shows mountains with water, cypress trees and flowers. There’s a heron on the inside door as well as some plant life resembling Venus fly traps.

The original artist was Omar Harris of Louisiana and his African influence can be detected in his work, particularly in the mask on the pole in the lower left corner of the vault’s main doors.

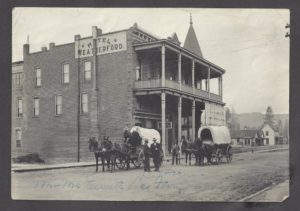

The large safe was built into the wall of Hotel Weatherford in 1897, but the hotel was not its first owner. It was hand-crafted by the Beard and Brother Safe and Lock Co. in 1884 for a firm called Cook & Lee. Later, it was owned by the First National Bank and C. A. Makler. When it found a more permanent home at Hotel Weatherford, the back of the vault was exposed to the alley and extreme weather.

When we bought the hotel in 1975, the vault was in pretty rough shape. The main body had large areas rusted out from seepage and dampness in the wall, where it spent most of its life. It had been in the bar for several years, too, and the doors were actually glued shut from the hundreds of drinks that had been spilled down the front. And the paint from the artwork had long disappeared. But we knew the old vault had a story to tell and felt it was our responsibility to refurbish this nugget of pioneering history.

There was only one man in the world who restored vaults as a full-time job. A. J. Brush of Magdalena, New Mexico, had been doing this work for 30 years. The project would cost $5,500. We paid half up front and Brush took the vault away. We didn’t see it again for two years.

During that time, detailed drawings and measurements were made of the lettering and artwork before the safe was sandblasted and the rusted-out areas stabilized. The main body was primed and painted, and a new metal skin was fitted over it and shrunk down for a tight, smooth fit. The doors were lightly sanded to remove the original varnish, which yellowed over the years and dulled the colors. The removal of this overlay revealed the vivid artwork, which was much brighter than we had expected.

Eventually, each individual letter and picture was laid out and repainted by hand. All the brightwork was polished and re-plated in nickel. The hinges were recast in American pewter.

The job of meticulously restoring the old vault took nearly 500 hours and the unique talent of A. J. Brush. In May 2000, the vault was returned to the hotel. Today, this beautifully restored antique lives in the Weatherford Hotel lobby for visitors to enjoy as a remnant of our American West heritage. FBN

By Henry Taylor

Leave a Reply