From the dirt to the treetops, scientists study samples as bacteria, DNA and insects may all be part of the formula for resilient trees in a changing climate

From the dirt to the treetops, scientists study samples as bacteria, DNA and insects may all be part of the formula for resilient trees in a changing climate

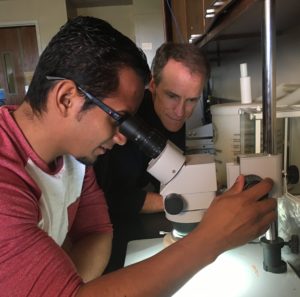

In a School of Forestry lab at Northern Arizona University, scientists are carefully unfolding large tropical leaves, examining exotic beetles and growing colorful fungus in petri dishes. The research is part of an international effort to give Panama’s dry tropical forests a fighting chance for future survival, and Panamanians the continued ability to make a living from forest products.

A changing climate, a recent unprecedented drought – the last two years have been the driest on record – and a history of deforestation have sparked global concern for the region’s dry tropical forests. A team of NAU researchers has answered that country’s emergency call to join in a massive tree planting project. Forestry Ecologist Kevin Grady is searching for the fastest growing and most resilient native trees.

“We’re looking at the qualities of 21 different species in terms of both their tolerance to drought and their ability to support ecological communities,” said Grady. “So do spider monkeys, for instance, that are rare and endangered in this part of the world, use them as well as insects and birds? We’re looking for the economic value of the trees, carbon sequestration value of the trees and nitro-regeneration potential of these trees. So, we’ve brought back a lot of samples from the plants to allow us to predict how these plant traits correlate to those functions of the trees that we’re interested in, such as drought tolerance.”

Researchers are grinding leaf samples into powder, which can be chemically analyzed. “We’re looking at the carbon in the leaves – the ratio of the carbon 12 to carbon 13 – and that’s going to tell us about drought tolerance of the tree species,” said forestry graduate student Yann Olivier Gouvancourt.

Gouvancourt also collected insects associated with the trees. He placed yellow sticky traps about the size of Bingo cards in treetops, 30 feet above the ground in some cases. When he removed them weeks later, the adhesive paper was completely covered in bugs.

“To effectively preserve and conserve tropical dry forests, we need to understand the entire community,” said NAU Forestry Entomologist Richard Hofstetter. “So, not only do we need to know what plants live there and how they perform, we need to know the animal community associated with them. These insects play important roles of pollination and nutrient recycling, seed germination and seed dispersal. Without the insect communities there, those flowers wouldn’t get pollinated, the seeds would not be produced and no matter what our efforts are to plant those trees, if the seeds don’t germinate and survive, then the forest would not continue.”

The researchers also are studying the forest floor. Forestry student Marcos Riquelme is from Panama. He is focusing on a particular tree called Terminalia Amazonia that is doing very well in his home country, despite the nutrient-poor soil in which it is growing. He believes bacteria and fungi are helping the tree get what it needs.

“It is baffling why Terminalia is growing at a really fast rate of about two meters a year,” he said. “We believe that a lot of that tree’s success is related to the associations it has with some of the soil microbes, more specifically fungal communities or mycorrhizas. We want to find out if this is one of those trees that’s going to be used for reforestation and if the same soil conditions that’s helping it grow can be applied to other plants to create a healthy community.”

Panama’s reforestation initiative is called Alliance for a Million. The Panamanian government’s goal is to plant 500-million trees on a million hectares in the next 20 years. NAU’s plant, soil and insect research is expected to help guide the ambitious project by identifying the best tree species for a dryer and warmer climate, along with their ecological support systems. FBN

By Bonnie Stevens, FBN